When I was twenty-three I showed someone around London, an American acquaintance who was six years older than me. Or rather, he showed me around London, although he’d never been there before. His name was Jack and he was a friend of a friend of the family. His family were wealthy publishers in America. I had met him once when he was visiting England briefly with his parents and sister. We got talking about London. He was fascinated by the novels of Charles Dickens and that led to a fascination with London, the history and topography and culture of London. He was also interested in the ‘Jack the Ripper’ case and had read a couple of the same books as I had. He wanted to go to the locations of the Dickens stories and ‘Ripper’ events, but didn’t have the chance as they were returning the next day. We talked for a little while and liked each other. He was educated in college and I wasn’t. He loved Pink Floyd and Monty Python. For about a year we had corresponded, by letters in the post between America and England, this being in the late nineties before everyone had email. Then in June he announced that he was travelling to Europe soon with his family and was stopping off in London for four days. He requested that I accompany him to the Dickens and ‘Ripper’ locations. So yes, sure, I said. I didn’t live in London but it was a short and cheap train journey from my home town. Jack was arriving on Friday, was leaving on the Tuesday, and wanted me to explore London with him on Saturday and Sunday. He would pay for all the food and drink and transport.

We were to meet up at noon on the Saturday at the foot of Nelson’s Column. I took the train into London and the Tube to Leicester Square. It was a warm sunny day. The fountains in Trafalgar Square shone and sparkled.

Jack was perched between the bronze paws of one of the Nelson’s Column lions, gazing down Whitehall towards distant Big Ben and Parliament. He had on an indigo shirt with the sleeves rolled up and a camera hung by his chest from a strap around his neck. When he saw me he stood up, grinning, and said ‘Hey buddy! Glad to be here! Glad you’re here!’ He reached down and we shook hands, then he pulled and I clambered up there with him. He offered a cigarette and we watched the shining fountains and the passing traffic and the strolling people as we smoked and he talked of his journey and his hotel. He liked to talk, and I liked to listen to him. He had a map and a pen and had marked off the route we were to take - through Covent Garden and along Holborn to Smithfield and the heart of Dickens country, over into Spitalfields and Whitechapel for the ‘Ripper’ sites, back through the City to the Bank of England, St Paul’s, Temple Bar, and then to Waterloo Bridge and Cleopatra’s Needle. He was excited, crackling with energy, jiggling his fingers and toes as we smoked and talked.

‘Shall we be away?’ he asked.

We dropped down onto the ground and set off.

We crossed the square and went by St Martin’s church, with the tip of its steeple high up gleaming gold above the green branches. Dappled sunlight moved merrily on the wide pale-grey pavements. People walked or stood all around, in light summer clothes. Statues on pedestals gestured mutely above the sauntering figures.

We turned into Chandos Place. From the open doors and windows of the pubs came a whiff of ale and food as people stood on the pavements beneath the flowerboxes with glasses in their hands, talking and smiling in the warm sun. We walked on the road, looking up at the smart brick and stone houses with their tall windows, first floor, second, third, and then, high up, along the housetops and beneath ranks of stately chimneys, rows of attic windows jutting out over the gutters and making you think of Mary Poppins and A Christmas Carol.

Passing into Henrietta Street, we came to Covent Garden. As we walked along the side of the Actor’s Church we heard applause and laughter and loud voices from up ahead and came out into the piazza, where in front of the church’s portico where the jugglers and clowns and acrobats perform a trio of entertainers held the attention of the crowd. People filled the piazza, families with children, smiling, squinting in the sun, calling out happily in response to the promptings of the clowns, who ranged about in their horseshoe-shaped space in front of the portico, manic and deft. Up on the Punch and Judy balcony, whose stone glowed with a gorgeous sienna colour like something from renaissance Italy, people stood or sat watching the performance. Two men on stilts, wearing top hats and tails and long pinstriped trousers, stepped heron-like among the crowds, looking impassively down on them. We ambled around for a little while, enjoying the crowds and the noise, then went underneath the balcony to the market building entrance, which showed us the long hall like a railway station with vast iron hoops receding far overhead under glass panes, and brick walls, and lamps suspended from long vertical chains.

Jack went off to walk around and take some photos and I wandered back to the piazza. The show was in full swing. The clowns, not circus-style clowns but the Chaplinesque music hall sort, wobbled about on unicycles in front of the familiar old church, with its huge creamy white-grey stone columns and its lapis lazuli clock. Children sat cross-legged in a row at the base of the columns or stood with their parents around the piazza. I smiled, thinking of the times when I was one of those children, fascinated by the performers, often taken in to participate in the routines when they needed volunteers from the audience. There would be acrobats who stepped lightly up onto your shoulders and then leaped onto a tightrope tied between two columns, or comedy magician acts, or puppet shows, or men who juggled with flaming brands or with meat cleavers. The latter I hated, and would watch the routine with a horrible cringing suspense, perpetually anticipating bloody catastrophe. Everything about the place seemed the same as it was then. I looked over to one side of the square and the row of tall 18th century houses over there seemed far off, in smart brick red and navy blue and creamy white, the attic windows along the grey roofs high up and distant and clear, a wisp of white smoke rising cheerfully from one of the chimneys. I looked over to the other side and again the sense of distance, as if it would take minutes to stroll over there to the houses. Seagulls went by overhead, crying out. There was a strange maritime sort of feel to the attic windows, distant and clear on the grey roofs, as if they were overlooking the sea, and a bracing feeling in the air like a sea air. This feeling I would always get when I came to London. And the exhilarating sense of space, of largeness and distance. It made me think of Gulliver, transposed to a fabulous larger realm. And Gulliver’s creator Jonathan Swift walked these streets and looked on these buildings and stood where I was standing, hundreds of years ago, watching the players in front of the church.

The chief clown, a stout fellow in a low topper and a tailcoat, was perched on a tall unicycle, six feet off the ground, pedalling it in lazy loops on the grey cobbles. His cheeks and nose were rouged red like a drunkard’s, his eyes looked around blearily, and the unicycle swayed and lurched dangerously. Balanced on top of his low-crowned hat was a pile of dishes, five or six of them, leaning this way and that way as he pedalled and swayed. There was a woman on a child’s bicycle with a drum strapped over her shoulders and a drumstick in each hand who pedalled around after the chief thumping and rattling on the drum. And there was a little, odd man, wizened and lithe, like a monkey, quick-moving, with a mop of greying dark hair and a beak of a nose and a crumpled black frock coat and battered black hat, like a real-life Mad Hatter. This little man kept picking up new dishes from a fold-up table and throwing them up to the man on the tall cycle. He took up a dish, spun it over and over with his fingers, faster and faster, flashed it in a blur back and forth between his hands, flipped it up and caught it on his elbow, let it slide off, nimbly snatched it inches from the ground, then tossed it spinning in the air and caught it on his upraised index finger. Then with a flick of his wrist the dish went arcing through the air towards the chief player on the tall cycle, who caught it neatly. The antic little clown took up another dish and spun it as before and then up through the air it went and the chief caught it with his other hand. He stood pedalling, rocking back and forth on the spot, bobbing and swaying above the heads of the crowd, with his arms outstretched and a dish in each hand, the pile of dishes on top of his hat nodding around precariously. Then he took his right foot off the pedal and extended the leg out in front. A frisson rushed through the audience. Hopping the unicycle with one foot on the pedal the chief carefully placed the two dishes on the shin of the extended leg. He stared at them, concentrating mightily, bobbing back and forth. The woman rattled out a drum-roll. All waited, silent, held in an agony of suspense. Then suddenly the man’s leg jerked and the two dishes sailed into the air, gracefully turned over, and clopped tidily, miraculously, onto the pile on top of his hat. The crowd erupted, jubilant, and the woman pedalled around beating the drum in celebration. And every time the act got right to the crucial moment, when the dishes were about to be flipped from the outstretched leg, and the audience waited in thrilled silence, the quick little clown with the Mad Hatter hat would try to distract the chief by sneezing loudly and drawing out a huge handkerchief, honking into it, or giving a dainty little ‘ahem’ like a vicar suppressing a cough, or seizing a violin and bow from the table and sawing out a vigorous merry jig, jumping around as if possessed by manic subversive glee.

I looked around at the people in the crowd. The streets around here were the theatre district and it was quite common to see a celebrity of some kind walking or sitting around. Almost every time I went to London there was one. Barry Cryer buying a newspaper at a railway station, or Bill Oddie flicking through albums in a record shop, or John Noakes sitting Shepless and forlorn on a Central Line train. One time I saw Jimmy Stewart getting out of a car by a hotel. I wondered idly if I would see anyone today.

Jack found me and we strolled around the corner of the Market building and into James Street towards Long Acre. We passed Covent Garden Station with its maroon tiles and old-style lettering. Voices rang in the narrow street, newspapermen called, bicycles tinged their bells as they glided by, tree-shadows moved on the sunlit brick walls and windows. Far up ahead, at the end of the street, was an odd thing, like a tall white-grey mausoleum, looming up, brilliant with sunlight, half-hidden by trees. As we got closer we saw a short tower, milky-white, rearing up over the surrounding buildings, with a large vertical slit in the middle and a circle in a semicircle above, like a single eye. The tower stood on three or four tiered steps at the prow of a huge stone building, which receded far down the street. The black vertical oblong with the shape like an eye above it gave the tower a weird anthropomorphic look and a comic, cartoonish appearance, like a huge tall head with a surprised face, a cyclops with an expression of shock or horror; like a giant fat one-eyed matron with multiple chins gasping in horror at something outrageous happening down the street.

‘That’s the Freemason’s Hall,’ said Jack.

The huge thing was still far off and we studied it as we walked. Jack stopped to snap some photos. I saw that the entrance, with its tall vertical oblong flanked by twin pillars, was a kind of ground-level copy of the tower high above it. As above, so below. The creamy oat-coloured stone bathed by the sunlight was quite beautiful and strange. Portland Stone, that was the material, I remember one of my teachers telling us on a school trip to London. Many of London’s most famous buildings are made from Portland Stone like this one. Just as we got near to where Drury Lane goes across the street, a crowd of men, in clean white shirts and black Derby hats, dozens and dozens of them, streamed steadily around the corners from the left and right, Freemasons all, suddenly and alarmingly right in front of and behind us and walking close on either side. They were heading across the wide open space in front of the building, towards the entrance. We looked around, startled to find ourselves suddenly in the midst of this black and white crowd, all men in their fifties or sixties or older, grey-headed, black-hatted, dignified, mayor-like, with V-shaped ribbons or chains like mayor’s chains over their chests. On and on they flowed, from both sides of Drury Lane. Returning from a parade or ceremony. Or a dinner, more likely, from the well-fed look of them. Next to me walked a fellow in his seventies, sturdy and oxen, Victorian-looking, square-faced, with white muttonchop whiskers and a moustache. The white shirts glowed on the broad backs in front, with sweat patches under the arms. They flowed around and past us, going up the steps of the Hall and passing between the twin pillars and through the doorway.

‘Whoa!’ said Jack, laughing. He held his hands up and jiggled the fingers around. ‘In the thick of it, right?’ He was elated at having had such up-close contact with these grave brethren with their hats and moustaches and regalia. He told me that this was the headquarters of English Freemasonry and the main meeting place for all the masonic lodges. We stood at the top of the steps by the doorway and watched for a while the stream of men coming up the street from Drury Lane and going past us into the Hall. Jack went over to one of the tall pillars flanking the door and put his palm flat at arm’s length onto it. I smiled, thinking of the monolith scenes in 2001. He stood there for a minute and then wandered towards the dark doorway where the men were still passing inside.

‘You think they’ll let me in?’ he said, smiling. ‘I’m just a nobody.’

Going down Great Queen Street by the side of the Hall we came out into Kingsway. We crossed the wide road, dodging around the slow-moving traffic, the cars and buses moving calm and slow like friendly dolphins all around us. We headed north, treading the wide pavement, which looked broad enough for about ten people. Trees lined the street, the trunks thrusting up near the kerb and throwing out leaf-covered branches above, a green canopy against the oat-grey stone walls. There was almost a Parisian feel to the place, the boulevard lined with trees and the smart off-white stone buildings. But the red double-decker buses, and the red telephone boxes, and the faces of most of the passers-by, were English. The ground level was mostly in shade, beneath the canopy of leaves and the high buildings, but here and there a bar of sunlight blazed right across the road, brilliant, bringing into momentary radiance the cars and the red buses that passed continuously along the thoroughfare.

We came to Holborn Station at the corner of the crossroads. Stalls lined the pavement outside the station, flower sellers, newspapers, snacks and cigarettes. We bought some cold drinks. Jack bought some cigarettes. From the station’s entrance came the sound of a recorded announcement, explaining clearly in a cut-glass accent like the Queen’s: ‘There are minor delays on the Hammersmith and City Line. All other lines are operating with good service.’ Pigeons moved about between the feet of the pedestrians or huddled like living grey eggs on the huge chewing-gum spotted pavement, throbbing and whirring. High up from a window down the street, a Union Jack flag rippled and turned as if in slow motion. A trio of taxi drivers behind us were talking.

‘So I says to ‘im, Blimey mate, what’s your game?’

Jack laughed, delighted. ‘Blimey,’ he said. It was one of the words or phrases he had wanted to hear someone say (‘Bloody hell’ was another).

We walked east along Holborn. As we went by the Old Red Lion pub we heard a brisk clip-clop of horse’s hooves behind and turned to see a pair of handsome glossy dark steeds drawing an open wedding carriage in which sat the bride and groom, the bride blonde and smiling and beautiful in classic English profile as they passed, the coachman sitting tall and elegant in his black top hat.

We walked on. Near Chancery Lane Station, where Gray’s Inn Road joins Holborn, by the side of the road on a stone plinth stood a small statue of a dragon, silver, rampant, rearing up above the traffic, showing its teeth, clawing the air. Its red tongue flamed out from between its jaws, it held out a shield displaying a red cross on a white ground. We stared up at it. This was the boundary of the City of London. From this point on was the City, the financial district, the Square Mile, ringed, or squared, by dragons on each of the main thoroughfares. We stood for a moment on the borderline, gazing up at the fierce winged sentinel. Through me the way. We passed over.

A few minutes later, just past lofty Prince Albert on horseback cheerfully doffing his hat, we turned left into Charterhouse Street. We were deep into Dickens territory. Jack walked slightly ahead, at a rapid pace, his head turning this way and that. Just past Saffron Hill we passed another City dragon, identical to the one at Chancery Lane. A minute later a short green-domed tower appeared up ahead, on the end of a long brick and stone arcade that receded right down the street as far as we could see. We had come to Smithfield.

Vans and lorries were parked on the tarmac outside the arcade or moved slowly past us. There was the loud beeping of vehicles reversing and a clatter of shutters rolling up and down and men calling and shouting. Men went in and out of doorways carrying crates and boxes. We walked alongside the building until we got to a vast, high arch with silver and red iron dragons glaring down on either side. Inside was a large open hangar, Victorian, like a railway station, with iron ribs curving high overhead and hooded lamps and the white disc of a clock with Roman numerals. Vans were parked in the hangar and men in white coats and white hard hats were unloading carcasses and great slabs of meat from them. There was a crash of pallets and the rumble of engines and the banging of great long pale pig or sheep or cow carcasses, their four legs stuck out in front and behind, onto little carts that were then trundled across the floor into adjoining rooms. The men shouted to each other or joked and laughed as they worked. Their coats were all wiped and rubbed and smeared with red all down the front.

We got talking to some of the men outside and discovered that the meat market was open only at night-time. The men were amiable and Jack chatted easily with them. All were Cockneys, from the streets round about. Two of them were near my age and the other two were in their fifties. One man, a stocky fellow with friendly downward-sloping eyes and a beaky nose that gave him the look of a good-humoured turkey, was a third-generation Smithfield porter. As Jack talked with them, naturally and affably, he watched their faces and mannerisms and listened to their accents and their turns of phrase. The older men warmed to him, their faces creased with smiles, their hands rested on their bloody smocks. Later he told me that he felt as if characters from Dickens novels and other London stories were standing in flesh and blood, literally, in front of him, talking with him. I listened too with pleasure. My mother’s family was from London and the accent was familiar and appealing to me. I thought of Smithfield at night, bathed in electric light, alive with the crash and clatter of carts and pallets and the throb of engines, the men young and old going back and forth shouldering massive hunks of meat, calling to each other, pushing their way between plastic sheets in doorways, walking under the strip lights, wiping their hands on their gory aprons, while the streets slept all around them.

Jack and I walked to the end of the Victorian arcade and went round it and back on the other side. Standing stark off to the south were three vast 1970s brutalist towers, the biggest and grimmest I’d ever seen, concrete and dark dull grey, hundreds of feet high. Concrete balconies stuck out like spines all up the sides; three gargantuan spined eyesores, depressing to look at. Like enormous prisons, or like government buildings from Nineteen-Eighty-Four.

‘I guess that’s part of the Barbican,’ I said. That area was destroyed during the Second World War and built up in the 70s.

We continued along the street by the market building. Crowds of people stood on the pavements outside the public houses, the flowers in the flower boxes glowed yellow and red, the bell-like brass lamps along the fronts of the pubs shone bright in the sun. Passing alleys disclosed evocative Hogarthian views of brown-brick houses and ancient church fronts and hanging pub signs.

We came to the south end of the hangar-like market entrance where we had watched the meat porters. Up on the building’s roof a Union Jack flag fluttered. Two more silver dragons scowled down from the sides of the high arch, their tongues darting red. Vans were parked by the entrance and porters crashed pallets and yelled to each other. We went over to a small round park across from the market entrance, with a low wall and a gate and a canopy of green leaves. In the centre of the park was a raised area with a statue on a stone basin, her arm upraised in benediction. We sat on a bench by the statue and lit up some cigarettes.

Jack was fired up with excitement. He talked about how Dickens described Smithfield, in Oliver Twist and Great Expectations, as a welter of noise and activity and filth, steaming, tumultuous, crowded with live beasts. He said that the present building wasn’t put up until the 1860s and before that, in Dickens’ time, there was an open space packed with wooden pens containing cows, oxen, sheep and pigs. The beasts were driven in great herds through the busy streets to Smithfield to be slaughtered. They spilled into the adjoining streets and lanes because the market was dreadfully overcrowded. Citizens were often trampled and crushed or thrown from their carts by rampaging cattle. The bellowing and shrieking and bleating all night in the streets kept the locals from sleep. Filth piled up and spread disease and sickness. Desperate local residents and business owners campaigned for better conditions at the Market and for the slaughterhouses to be closed down and moved elsewhere. But the City of London Corporation turned a blind eye because of the massive profits the Market generated. More and more beasts poured in, every day, bellowing, obstructing and fouling the streets, and it continued so that the Corporation could rake in the millions in revenue. Finally after much pressure, including from Dickens, the Market and abattoirs were moved out of the area, and a decade or so later the Market reopened with the new building, handling only pre-slaughtered animals.

Most of London’s and England’s meat, roast beef of old England, came through Smithfield, or at least it did until quite recently.

It wasn’t only livestock that were slaughtered at Smithfield, Jack continued. For hundreds of years this was one of London’s foremost sites for public executions. The Protestant martyrs were burned at the stake here, right where we were sitting, or very near, during the reign of Mary I. Wat Tyler, one of the leaders of the Peasant’s Revolt in 1381, was killed on this ground while negotiating with King Richard II. And those convicted of high treason were executed here, before a crowd, as a dire example. This was where William Wallace was hanged, drawn, and quartered (Braveheart had come out a few years before). They would do the executions during the Fair, the famous, or notorious, Bartholomew Fair that took place here in August, so that there was a large crowd and everyone saw what happened to those who raised their hand against the Crown. Jack described the traitor’s death thus:

The condemned man was tied naked to a sled and dragged behind a horse through the streets, from the Tower of London across the City to Smithfield. Along the way crowds lining the streets would hurl abuse and rotten food at him. Here at Smithfield the prisoner mounted the scaffold, facing the crowd, the noose was placed around his neck, and after some preliminaries he was suspended, slowly strangling, for a time, after which he was lowered to the ground while still living, and taken to the butcher’s block. He was castrated with a blunt blade and his parts burned in a bowl of fire in front of him. Then the executioners slit his belly open and cut out his guts and organs.

‘Bloody hell,’ I said.

Jack smiled grimly and went on. The man’s entrails were burned in front of him. His heart was cut out and burned. Then his body was lopped into five pieces and his head was struck off. Up on bridges and thoroughfares went the head and limbs, grim tokens of admonition for the passing multitudes.

My mind reeled with the grossness of it. I imagined the body being hacked up in the street like slabs of meat, dogs licking the blood off the cobbles. Here comes a chopper to chop off your head.

‘Of course treason was defined by the Crown as what went against the Crown,’ said Jack.

‘And what if the Crown itself committed treason?’ I asked.

‘They’re not going to hang themselves,’ shrugged Jack.

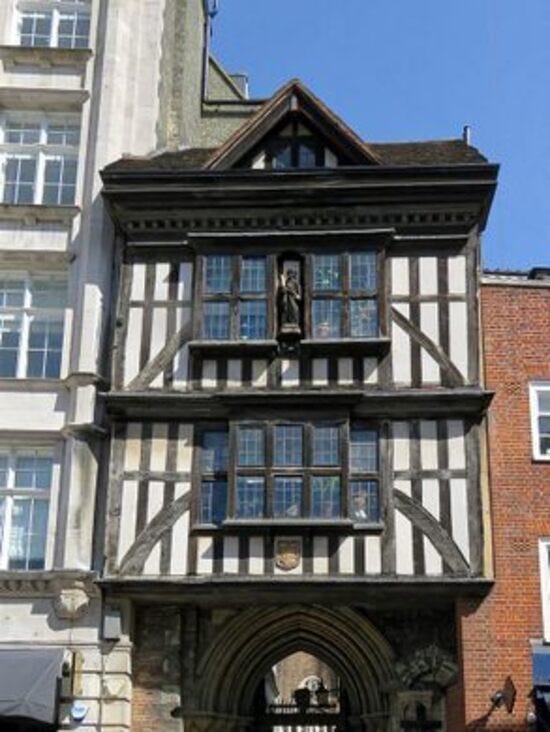

We went out the park gate and around the outside of the park. On the wall of St Bartholomew’s Hospital was a memorial for William Wallace. Jack indicated a narrow Tudor gatehouse with timber beams. He told me legend had it that over there - not that particular building but the one that was there before it - Queen Mary would eat dinner by the window while watching people being burned at the stake. I thought of black smoke whirling around the square, the roar and crackle of the fire, the screaming, the flames reflected in the windows, the calm figure watching. The attic window right at the top of the house looked weirdly like an eye, as if the house itself were watching the square.

Down the street called Little Britain we headed. This was where, in Great Expectations, the lawyer Mr Jaggers’ offices were; a ‘gloomy place’ with ‘distorted’ houses, wrote Dickens, but they were long gone and it was mostly modern offices now. People stood drinking and smoking outside the pubs. We caught a view of the huge dome of St Paul’s Cathedral far down the street. Then we turned left and found ourselves in a gloomy little traffic roundabout with the black brick rotunda of the Museum of London in the middle of it. Looming up far behind was one of the vast brutalist towers we had seen from Smithfield. We walked east alongside crumbled chunks of the old Roman wall, traffic whooshing by on the right, then turned left into the Barbican complex.

Past new office buildings we went, reflected in their glass fronts. Then grey 1970s concrete terraces and balconies that were reminiscent of multi-storey car parks. The three brutalist towers stood grey and monumental like enormous spiny obelisks. Going round a corner we saw ahead a medieval church, of light-coloured stone, sitting there almost surreally amidst the brutalist concrete and the 80s shopping-precinct-style paving. It was as if it had been blown from elsewhere by a tornado, like Dorothy’s house in The Wizard of Oz, and set down in this modern blandness. Jack went over to the entrance to see what it was called.

‘St Giles Cripplegate,’ he read. He laughed. ‘Hey, don’t you love these names? Cripplegate.’

I did. The street names in the City and elsewhere in London had something about them that was quirky and evocative, something wry and English, like the phrases in Nursery Rhymes. Bread Street. Milk Street. Pudding Lane. Shoe Lane. Gutter Lane. Cripplegate. Houndsditch. These medieval or Jacobean street names and pub names evoked in my mind a realm of kitchens and cooks, tailors and cloth, cobblers, candlesticks, bells, and clocks. Kettles and pans, brickbats and tiles. Said the bells of St Giles. Like Shakespeare too. The phrases, the sounds. Within the hollow crown that rounds the mortal temples of a king. Something universal but also uniquely English-sounding. Smiling damnéd villain. You could read it, act it, in any accent, but it just sounded best with an English one. Most smiling, smooth, detested parasites, courteous destroyers, affable wolves, meek bears. Shakespeare lived in a house two minutes from where we stood, hundreds of years ago. Whoever he was, he would likely have at some point stood here right where we were.

We went along Silk St and turned right, heading north.

‘You want to be a writer, don’t you?’ Jack said.

I nodded.

‘What kind of writer do you want to be?’ he asked.

I shrugged. I wanted to maybe write a screenplay. I had become interested in making films.

‘What about?’

I didn’t know.

‘Do you want to be a conformist or a nonconformist writer?’

I didn’t know what they were.

‘Do you want to defend the establishment, or go against the establishment?’

Umm. I wasn’t sure. A bit of both maybe. I didn’t really know what the establishment was.

Jack thought and then said, ‘I’ve written some things. Not much, yet. It can take a while to find your voice. You know you want to write something, but you don’t know what?’

I nodded.

‘You’re young,’ he said. ‘It takes a time before you have the experience and knowledge. You didn’t go to University, did you?’

I shook my head.

He smiled ruefully and said ‘Well, I’d say in some ways you’re fortunate.’

We walked on a bit. Jack said, ‘I’m kind of the black sheep of my family. They think I’m nuts. They support the establishment. My dad’s a mason. He wanted me to join. I told him No. I just hope they don’t, you know, excommunicate me or put me in a psychiatric ward or something.’

We were walking along Bunhill Row. We turned right through a black iron gate and onto a railed dappled path under a canopy of green leaves. A signboard with the City shield and dragons told us ‘Welcome to Bunhill Fields Burial Ground’. Behind the railings on both sides were many little gravestones, pale and grubby, greened or sooty, standing or leaning like silent grey ghosts among the grass.

‘This is the Nonconformist’s graveyard,’ Jack told me.

‘This is where they throw you if you don’t conform,’ he said. ‘On the bonehill.’

Here and there among the shabby stones an obelisk glowed in a patch of sunlight. Birdsong chimed out. Squirrels darted through the ferns, leapt onto tree trunks and spiralled like fireworks up into the rustling branches. We came to an open space and found in a corner by the railings a small chalk-coloured tomb with a mossy stone effigy of a man laid out on top. ‘John Bunyan’ read the name on the tomb. We looked at the calm stone face with its eyes closed in profile. One of the sculpture’s hands rested on a book. A squirrel on a branch watched us, bright-eyed, round-cheeked, quivering with energy.

‘Well, here he is,’ said Jack thoughtfully, ‘Mr Bunyan.’

He leaned over and laid his palm for a moment onto the stone hand.

I had an urge to touch it too, though I didn’t know who the man was. I leaned in and put my palm onto the rough mossy stone.

Jack walked around the tomb taking photos. On my side was a relief sculpture of a tired-looking man clutching the top of a stick on which he leaned, bent under a heavy load on his back.

‘What is this?’ I asked.

Jack pointed at his eye and then at the other side of the tomb. I went round and looked. The man was raising himself upright and the heavy load had fallen off his back and was on the ground.

We walked on, talking. Under the branches of an oak tree stood a tall white obelisk, like a giant chalky matchstick, with a little blotched-ochre headstone standing dwarfed a few yards away on the pavement by the side of it. On the obelisk was inscribed ‘Daniel Defoe. Born 1661. Died 1731. Author of Robinson Crusoe.’ Jack put his hands onto the obelisk and smiled ruefully, thinking. After a little while he went to the sooty ochre slab and knelt on one knee to read the inscription.

‘Mr William Blake,’ he said.

He put his other hand on the headstone and, looking at the inscribed letters, again went into a thought for a few moments. Then, coming out of his reverie and looking at the stone, he said ‘I wander through each charter’d street, near where the charter’d Thames does flow.’

He stood up.

‘Shall we go?’ he said.

Our feet walked us down the pathway to the eastern gate. Through we went and onto City Road and north to the Old Street Roundabout. Jack was full of energy, like a dynamo. He smoked and talked and snapped photos on his camera. Great Eastern Street, straight and long, stretched out far in front of us, pointing deep into the East End. Traffic whooshed up and down the road. The sun shone warm and full. I wiped sweat from my forehead. We travelled on past office windows and bland 1960s brick buildings. Far ahead loomed some dismal post-war tower blocks, shabby and grey. Jack went into a little shop to buy some cold drinks. While he chatted with the old couple behind the counter my eyes wandered over the newspaper rack. Replicated on half a dozen front pages, the boyish face of Tony Blair smiled and smiled. Police sirens wailed and pulsed in a nearby street. The sun was warm as milk on my back and the back of my neck. Jack came out with cold bottles of fizzy pop and we drank, turning our faces up to the warm light, sweat trickling in our eyes. On we walked. We went across Curtain Road, where the first two purpose-built theatres in London had stood, hundreds of years ago. Shakespeare’s company of players performed there.

Traffic rumbled and snored past, motorcycles rasped, buses squealed and hissed. High up above in the blue sky a helicopter clattered. The road opened out and there were long wide vistas of streets receding into sunlit distance. Shadows slanted across the roads and pavements. The sun flashed on high office buildings which were reflected in the windows of the shops and houses we passed. This was where the financial district jostled up against the old East End. Here the pavements were a little grimier, here bags of rubbish and boxes were piled up outside the shops, here were patches of waste-ground behind fences of battered wooden boards or sheets of corrugated iron, covered in sprayed graffiti; spiky weeds stuck out here and there along the tops of crumbling brick walls. Some of the old Victorian buildings had a blasted look, as if they had been bombed or burned, some had boarded-up or broken or empty windows raw like eye sockets. I thought of the slums I used to see when I was a child, in the 80s, coming into London by train through the East End and looking down onto blasted shells of houses with yards that were a chaos of shattered slates and planks and dustbins and piles of filthy rags. Like a bomb had hit them. And maybe it had, forty years before, and no-one had cleared it up yet. I remembered patches of waste-ground scattered with rubble and covered with weeds and flowers, and ancient ruins of Victorian factories with smashed windows. We trekked on. Music and voices flowed from the open doors and windows of pubs. Old derelict factories and industrial alleys and yards went by, next to smart new office blocks. As we went past a large old market building on the right we saw ahead a white limestone church steeple rising above the roofs and chimneys across the road.

‘Here we are,’ said Jack, ‘Christchurch, Spitalfields.’

The front of the church rose tall and narrow, gleaming, a white exclamation mark placed among the blasted brown rows of Georgian houses and shops. Two pairs of tall white Roman columns stood forward on the porch, flanking the door, like the forelegs of a couchant animal. Light and shadow slanted elegantly over the facade. Portland stone again. At the end of the street which went down by the side of the church was the Ten Bells pub, the walls sun-baked, seedy-looking with patches of flaking and peeling paint. I had been here before, once on a ‘Jack the Ripper’ tour on a school trip when I was fifteen, and again a few months ago to take photos to send to Jack. We crossed the road and went up the steps of the church to the porch, between the pedestals of the columns. Jack laid his hand on one of the pillars for a moment and then offered a cigarette and sat on the top of the little wall at the edge of the porch, leaning against the warm stone of the pedestal. I sat at the top of the steps.

I had started to feel a half-pleasant ache in my legs and thighs from the walking. We had been out for about three and a half hours. We smoked and watched the street below and gazed at the buildings and the walls of the houses, blotched and blasted and glowing golden-brown like tobacco. A police or ambulance siren bayed and ululated some streets away, in some city canyon of glass and brick, loud and long. Traffic roared and growled or waited rumbling at the traffic lights by the church. Music thudded from the open door of the pub. My eyes squinted in the sun, my head felt dazed and heavy from the accumulation of the summer day. The pulsing city teemed all around us. High up in the sky the lights of a jet plane flashed as it cruised by overhead.

After a time we got up and went down the steps and into the little railed park by the side of the church. Jack said this was called ‘Itchy Park’ in the nineteenth century because all day it was full of flea-ridden, diseased homeless people who came in to sleep. At the back corner of the park a motley jumble of bumpy old houses stretched away down the back side of a street, dingy and raw-looking. Somewhere a dog barked over and over again, desolately. The windows in the old brick wall on the edge of the park had iron bars and looked like windows on a prison. In the street alongside the park entrance stood a stone obelisk by a red telephone box, which was plastered with cards advertising prostitutes. On the other side of the street in an open second-floor window a man in a string vest leaned his elbows out over the dirty paint-peeled frames, smoking above the traffic. Jack was looking for Dorset Street, the ‘worst street in London’, as he called it. ‘It should be over there,’ he said, pointing right across the street. We dodged over the road between cars and buses, the air thick with exhaust fumes. The street across from the little park was just an unnamed service alley with on one side the back wall of a 1970s car park and on the other a storage area with large green metal-shuttered doors.

‘This is Dorset Street?’ Jack said, crestfallen. We walked all the way down it in thirty seconds and went back. This was the site of the last of the ‘Ripper’ murders, that of Mary Kelly, in her little room at the back of the street in Millers Court. We estimated that Millers Court had been located about where the green-shuttered storage bay was now. Jack had seen film footage of the room from the 1920s and assumed that it would still be there. He told me about Dorset Street, what it was like in the nineteenth century. He said that he was fascinated not so much by the details of the murders themselves, as by the things he had learned about the surrounding area and the way the people lived. In the 1800s the streets around here were some of the worst slums in London. Dorset Street was full of lodging houses, or ‘doss houses’, the cheapest form of accommodation available. In the lodging houses the floors in every room were covered with narrow beds, packed together, with high wooden dividers between them, looking a bit like open coffins, and people paid tuppence to sleep, or try to, in these coffin-beds, in each room surrounded by ten or fifteen other people. In Dorset Street many of the inhabitants of the doss houses were criminals who were looking to recruit young people and others into their gangs. They would flash money around and offer booze and food and tobacco and befriend the youths, corrupting them, teaching them how to pick pockets and pick locks, how to climb in through a high open window, how to use a knife or straight-razor in a fight. There were so many gangsters and thieves in short little Dorset Street that police would only enter it in groups. Murderers and other fugitives took refuge here and swaggered the street, roaring drunk. It was said that every house in the street had had a murder in it, and one house had had a murder in every room. And the most infamous murder was Mary Kelly’s, in the grimy court behind the street, in November 1888. Now, a hundred and ten years later, it was this blank, anonymous, unremarkable little passage between Commercial Street and Crispin Street.

I thought of Fagin’s band of young pickpockets in Oliver Twist and of Bill Sykes, and of the night porter in The Elephant Man, the character played by Michael Elphick, burly, cocky, gravel-voiced. Brought up in the lowest drinking dens, surrounded by crime and violence. These big, burly ruffians, with hoarse jeering voices and boxer’s snouts, rough and forcefully redolent of violence and criminality, this was a type you sometimes encountered in the East End and elsewhere in London, the modern version of the Bill Sykes type. The type you immediately knew to avoid eye-contact with just from hearing their voices. You could see them at the doors of nightclubs, coked up, roughhousing with each other, sniffing loudly and grinning and cuffing each other like lion cubs; you saw them outside rock concerts or West End theatres touting tickets, swearing, sneering, as if daring anyone to challenge their rudeness. These men seemed to me like real-life outlaws in Wild West films, lawless, like Liberty Valance, ‘bad men’. These were the streets where they lived and drank, gangland territory. Dorset Street’s final murder was the gangland killing of a boxer in 1960, not long before the street was demolished. Less than a mile from here was a place notorious for its criminals - Bethnal Green, where the Kray twins were from.

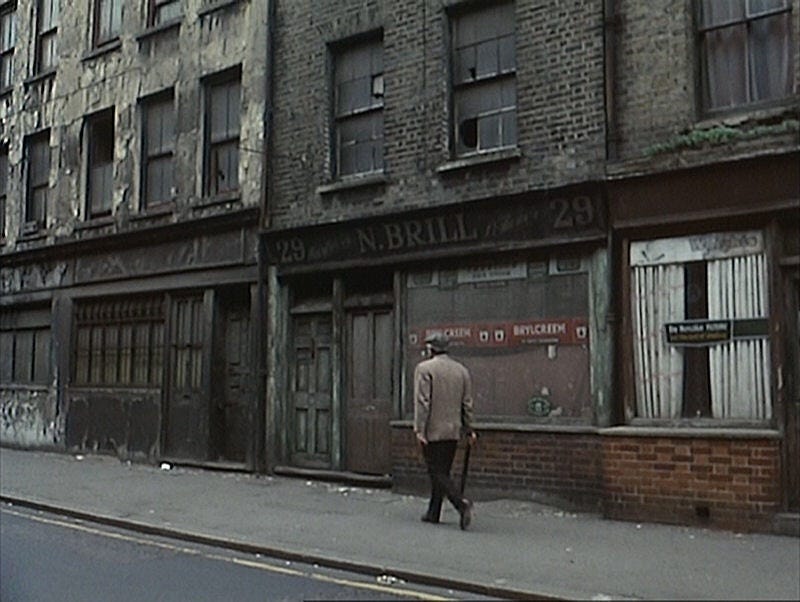

We walked up and down Whites Row, which was the next street to Dorset Street and the same length and width, but with old brown-brick tenements on the south side, like Dorset Street would have had. We turned left at the end, crossed the road, went back past the church and the pub, and turned right into Hanbury Street. Here again most of the south side still had the old Victorian or Georgian buildings, but the north side was all 1970s smooth brick and concrete and glass. We were looking for number 29, where the second ‘Ripper’ victim, Annie Chapman, was killed. We had both seen film footage of the street from the 1960s, where the actor James Mason goes to see the house and the yard at the back where the murder occurred, and remembered the ghastly dismal, leprous look of the houses, filthy and raw.

All gone now, just a bland 70s brick wall, scrawled with graffiti, ‘29’ stencilled onto one of the grey windows.

‘Ah, well,’ said Jack, disappointed again.

Vans and cars and bicycles moved down the street. The air rang with voices and music from the pubs. We turned the corner into Wilkes Street and then left into Princelet Street. In these streets the houses were all eighteenth or nineteenth century, architecturally similar to the eyesores in the James Mason footage, but cleaned up, smartened, the heavy wooden house doors neatly painted and the windows intact and clean with painted frames. The brick walls, old and blotchy and baked and scumbled with soot, but washed and scrubbed, glowed in the sun with siennas and ochres and umbers, with a strangely soft and dusted honeyed look.

In eerily empty and quiet Princelet St we walked past a row of tall windows with painted wooden shutters. One windowsill had a row of green glass bottles with flowerstalks in them, silent in an oblong of sunlight. In another window a tabby cat reclined on the warm sill, blinking out benignly at us. In another a jester doll with cap and bells and grinning Mr Punch face peeked out, moulded with sunlight against a dark background. I looked around at the scarred motley brick walls and wood doors and iron lamps and tall elegant silent windows, all around us, like being in another world. In one upstairs window could be seen books and a piano.

We went into Fournier Street by the side of the white church, walked to the end and in through the open door of the Ten Bells pub. The place was crowded and clamouring with voices. We bought drinks and sat at a table near the window. We drank and smoked in silence for a while, looking around, heavy and drowsy with digesting the experiences of the afternoon. We bought more drinks. This was one of the pubs that the ‘Ripper’ victims had frequented in the 1880s. All of them were prostitutes. These streets were where people who had lost everything ended up. They were swarming with whores, pimps and gangs. Many of the ‘lodging houses’ were used as brothels of the lowest sort. Most of the prostitutes here were alcoholics who spent their income on gin and a bite to eat and then lodged in the cheapest doss houses, or in the street if they drank away their doss money. Alongside all this there was industry and trade going on, breweries, foundries, factories, sawmills, slaughterhouses, saddle-makers, boot-makers. Jack and I talked about the Whitechapel slums and the films and stories that were set in them. We talked about The Elephant Man, the scenes where Dr Treves goes into the slums, the strange nightmarish industrial rumbling and clanking and thudding that permeates the film, as if the East End was a giant powerful machine or beast. Not far away in Whitechapel High St was the hospital that was the film’s main setting. Jack told me that he used to really like the film, until he read about the real Joseph Merrick and discovered that all the scenes of abuse and cruelty in the film are fictional. In reality Merrick exhibited himself in carnival shows voluntarily, he was friends with his manager and lived with him in his house, and he took fifty percent of the profits. When the hospital where he went to live made an appeal for donations of money to secure his lodgings there, London’s poor people donated enough to keep him. The wicked manager ‘Mr Bytes’ was fictional, and the brutish hospital porter, and the scenes where Merrick is beaten and kept chained up like an abused animal without talking to anyone for years.

‘Really?’ I said.

‘I mean, it’s good drama,’ said Jack, ‘It’s good storytelling. But it kind of spoiled it for me, finding out how they made it much worse than it really was. Like with Midnight Express, you know? And a bunch of other stuff.’

We talked about films and Hollywood and Freemasonry. Jack said that he thought Jack the Ripper was a Freemason. I had heard that, but didn’t know much about it. He said that masonic phrases were found written on a wall in chalk near one of the murder scenes, but the policeman in charge ordered them to be wiped off. He talked about how the police force was run by masons, and all the top jobs in the establishment. He told me that the Ripper’s strangling and disembowelling of his victims was similar to punishments described in the Mason’s initiation oaths.

‘And at Smithfield,’ I said.

We wanted to drink and talk longer but we had a way to go. We headed back down Princelet St to Brick Lane. Here were lots of immigrants, South Asians, and lots of curry restaurants. Men in red jackets stood outside the restaurants inviting passers-by to enter. Foreign languages sounded out all around. Down near the end of Brick Lane we turned into Thrawl St, once a squalid row of Victorian doss houses, now a bland little 1970s housing estate. Down Flower and Dean Walk we went, out into Wentworth St, and then down a little cobbled street that I recognised from the ‘Jack the Ripper’ tour I’d been on. And here was a ‘Ripper’ tour now, twenty or so people with cameras standing in the road listening to a talking gesticulating bearded man in a black hat. ‘The discovery of the horrid corpse,’ he was saying portentously as we went by, making us chuckle. The road narrowed to a cobbled lane and we went into a short tunnel under a grimy little arch, plastered with posters and notices, and out onto Whitechapel High Street.

We stood for a moment on the huge pavement, looking around. I had been past here dozens of times, in a car or coach. This was where the East End started to blend into the financial and business district. To the west office blocks rose up on either side of the wide road. To the east was Whitechapel and the rest of the East End, miles of it, through Mile End and Stepney to the Docklands and Canning Town. The city roared softly. Red buses, black taxis, cars, vans and lorries moved steadily down the road. People flowed past. A ragged man sitting on the gum-blotted pavement with his legs in a sleeping bag asked passers-by for spare change. Someone was pushing a metal cart which clashed and chattered over the ground. We walked west, towards Aldgate. Long lazy shadows slanted from the lamp-posts and bus-stops. After a minute or two it was mostly post-60s office blocks, glass and concrete. I was feeling the half-pleasant ache going deep in the back of my thighs and my knees, like after a long workout, and my feet were a bit tender. We must have walked at least six miles. The reflection of a cruising jet plane rippled gracefully over the glass panes of one tall office block. A shrill police siren whirled some way off, got nearer and nearer, grew massive and unbearable, and passed, changing key, whooping and trilling, heading towards Whitechapel.

Where St Botolph St went across we saw a little silver City boundary dragon on its plinth. This was the eastern edge of the City. We passed. Back in the dragon’s den. A minute later the tower of St Botolph’s church appeared, square and brown in its railed garden. Just past the church we turned right into Mitre Street. Here Catherine Eddowes, the fourth ‘Ripper’ victim, was murdered. His second victim that night. She was picked up near the church, which was always surrounded by prostitutes, brought here, and frenziedly stabbed and slashed to death. All modern office buildings it was now, and flat grey modern paving, a few trees, and the asphalt playground of a red-brick school behind a high iron gate.

We went back to the main road. Here by Aldgate Pump the street divided into two forks, twin canyons of pale Portland stone and office windows. We took the right fork into Leadenhall Street. Weird to be walking in this international finance centre, between cream-stoned bank buildings and glass-fronted insurance offices, only two minutes or so after standing where Jack the Ripper butchered Catherine Eddowes. From the gutter to the high financial strata in no time. This street was where the East India Company had its headquarters here in the 18th and 19th centuries. We tramped on for several minutes. In this city canyon the sound of voices swirled faintly, the noises of the rumbles and snarls of traffic were amplified and uncannily reverberated, ghostly whistles and clicks sounded from far off, strange disembodied knocks and clanks seemed to come from the sky every now and then as if a demiurge were working leisurely above the city.

The street widened and there was more traffic. Men in suits walked by carrying briefcases. We went underneath the gigantic new Lloyds Building, which had the same energy as the brutalist Barbican towers, colossal and grim and ugly. We looked and passed by in silence. A little further on we came to a crossroads and turned right into Bishopsgate, walked on for a few minutes, my aching feet sore in their tired shoes, and then left into Threadneedle Street. I, said the beetle, with my thread and needle. Here were more smart old bank buildings made from well-cut blocks of smudged-oat stone. After a while as we went by the side of the Royal Exchange we saw ahead on the right, towards the end of the street, a long, high wall, and above it the huge white fortress-like bulk of the Bank of England, with its classical facade high up shining against the blue air. Here the street opened out into a wide vista of hazy blue sky and gleaming walls and columns of Portland stone, bright and striking, like a Turner painting. In front of the Royal Exchange a spit of land, with benches and little squares of greenery and monuments and elegant old black Victorian lamps, projected out towards Bank Junction. Red double-decker buses and black taxis arced round the junction, flowing down King William Street towards London Bridge. I planked my body onto one of the benches.

I marvelled again at the proximity of these battlements of international finance to the brick alleys of Whitechapel and Spitalfields. From Dorset Street, that den of thieves, to the Bank of England, that fine institution of honourable men, was less than a mile’s distance. From Jack the Ripper, just a hop skip and jump to the capstone of the financial pyramid. At the head of the Chamber of Commerce. I looked at the statue of Wellington looming over me, which in turn was loomed over by the huge front of the Bank behind it. Your most obedient servant. All the king’s horses. England expects. My eyes wandered over the frieze on the pediment of the Royal Exchange. Commerce, crowned, flanked by merchants and bankers. The Earth is the Lord’s and the fulness thereof. There were tons of gold underneath these streets. London streets paved with gold. I had seen in a tv documentary the gold vaults underneath the Bank of England, long corridors of stacked-up pallets full of gorgeous soft-gleaming bricks of it, hundreds of thousands of them. Vaults of treasure, heaps of shining gold, dragon-guarded; the Bank flourishing over them with its grinning mouth. The king in his counting-house. Thousands of barrels, laid below. To prove old England’s overthrow. Gold-plated sin, plate sin with gold. What was that from? Shakespeare. Plate sin with gold, something something shove by justice. Breaks the lance of justice. Something like that.

I thought of the Monty Python film where the old City accountants stage a mutiny against their corporate overlords and launch the bank building into motion like a pirate ship; same kind of building as these, same streets. In the film the accountants/pirates sail to America where they behold towering walls of glass, colossal Manhattan skyscrapers, hundreds of feet high, an alien world. That was America, they had their grand canyons of glass, boardroom meetings up in the clouds with the city spread out far beneath, like being on a glass Olympus; we had our grand old sooty stone buildings and our ancient churches and our Victorian clocks with Roman numerals and our medieval street names and our homely old gents in waistcoats and ties. I loved these differences, these national characteristics, those of other nations as well as those of mine. Thank god we still had these qualities and traits, thank god this place had not been Americanised. I imagined colossal glass towers looming over these buildings, dwarfing them, overshadowing them. God, no. America had its way of doing things, and that was fine. And we had our way of doing things, and that was fine too.

I leaned my head back on the bench and closed my eyes, feeling the red warmth on my face and eyelids. My tired legs throbbed. Rest here for just a minute. Voices swirled around me. Old English voices, a man going by with an accent like Roger Moore. James Bond. On Her Majesty’s. I thought of City gents with bowler hats and long folded umbrellas. You still saw them round London sometimes. The old gent in Genevieve. Steed in The Avengers. Gorgeous Emma Peel. The noises of the street seemed to get further and further away. Emma Peel in a summer dress leaned in, smiling, whispering something.

‘Hey!’ Jack was patting my shoulder. ‘Wake up, buddy. You can’t sleep there!’

I stared, dazed, blinking. I had been on the verge of dropping off. Jack stood over me, ready to leave.

‘Think you can make it, pilgrim?’ he said, grinning.

He held out his hand and I gripped it at the wrist, he pulled and I stood up slowly and achingly. My legs felt like slabs of meat. But still human, at least.

‘Up on your pins,’ Jack said.

We crossed over the road, went along the wall of the Bank, and headed west up Cheapside. Where is Becket the Cheapside brat? More nice old Portland stone above glass office fronts or shops. There were gentlemen’s cigar shops and umbrella shops and old-fashioned tailors shops. The passing window of an old-style chop house showed me a portly man in a suit eating beef in peppercorn sauce with fried tomatoes and onions, and I realised I was very hungry. A goodly portly man. Falstaff in Shakespeare’s Henry IV; these streets, the taverns and inns in these streets, were his stamping ground. His ‘manor’. You shall find me in Eastcheap. As Jack and I stood for a moment near St Mary-Le-Bow church, looking around, a pleasant voice said from the side: ‘Can I help you? Are you lost?’ A white-haired City gent in a bowler hat stood there politely inclining towards us. ‘No, we’re on the right way, Sir, thank you,’ I said. ‘Righto,’ he said cheerily, ‘Good day to you.’ And he moved on. We stood grinning, watching his immaculate form walking away, delighted to be the recipients of the unexpected little display of old world manners, the fine contact with a living particular embodiment of an archetype. It was like being included in something, making a connection with something.

As we walked on I was aware of some sort of commotion, in the air, up ahead. There was a sort of roiling in the air, a weird, powerful clash and jangle, coming in gusts and fading again, gradually growing clearer and louder as we walked on. I realised it was church bells, clamorous and full-throated, the largest church bell sound I’d ever heard. But familiar, as familiar from television as the image of St Paul’s Cathedral. The bells of St Paul’s were in full cry, up ahead, tons of clamouring iron churning the air, crashing and booming. As we came to the junction of Cheapside and New Change, there it was, across the wide expanse of road - the lead and stone dome with its frosted look, huge, sooty and smoke-blackened, English, daily familiar to every British person from the Thames TV ident and from hundreds of tv programmes, posters, postcards, newspaper photos, and now emphatically present before us in the original, scorning all its paltry imitations, announcing itself with this tremendous outpouring of sound, this musical storm of plunging iron.

We crossed over and went under the monumental, majestic clashing and booming, by the churchyard with its trees and black iron railings, and walked along the side of the cathedral, which was going like the clappers, the sound crashing upon us in wave after wave. Wonderful and stirring it was, huge and awesome, like the folding into each other of immense toppling dominoes of noise, and my body rang with it. We passed right under the enormous bell-towers and out in front of the cathedral, which rose up like a sheer cliff, the familiar old cream-white Portland stone, the two storeys of huge classical columns, the twin bell-towers pealing forth their rich, shattering clamour, the air around them seeming to shiver with vibration. Little flocks of birds spiralled and raced madly around the top of cathedral, as if exulting in the tumultuous riot of frequency. We climbed up the steps. Jack stood with his back against a stone column, and I sat on the top step. Over on the left was large, elegant grey-stone Condor House, beautifully dappled with bars of glowing golden sunlight. At street level the lights in the shops shone through the big windows, people walked by in profile against the scrolled doorways and pale grey stone. People walked up and down the steps of St Paul’s or stood or sat, or walked around on the paved area in front of the cathedral. On a plinth was a stately, ghostly stone statue of a queen, and there were handsome iron Victorian lamps. The bells hurtled on, like gigantic crockery smashing musically and continuously. Children ran about or stood gazing up at the massive edifice. On a bench sat an old man with his hands on his walking stick in front of him, calmly facing the wall of sound, contentedly surveying the scene. Jack went about taking photos. After a while he wandered to the open door of the cathedral and went in.

I got up and walked down a few steps and stood looking straight up at the top of the cathedral, my head all the way back. Up there on the summit, between and below the clashing bell-towers, the saints and apostles sat as if stunned, far above, gesturing mutely. Flocks of birds darted past against the sky behind them, disappeared behind the cathedral for a moment, then raced out again at another angle, swerving as one, plunging back again, as if surfing the riotous waves of sound. The gorgeous din thrilled through my body. There was one great, deep iron bong, low and chesty, sounding over and over, strong and regular, like a pulse. Around this, full-throated bells made mesmerising descending and ascending patterns of vibration. And through and around all of it was a mad crashing jangle, like the vast iron doorbells and clocks of a multitude of sky-giants all chiming at once, in repeated figures that seemed to shift and break off and merge weirdly almost like fairground music, teetering crazily on the edge of disharmony and disaster but always maintaining a dizzy equilibrium. All of it was like a kaleidoscopic tumbling to the edge of chaos and then folding back and merging and retumbling, an ongoing cascading apocalypse, like the perpetual smashing of a colossal tower of dishes, in the notes of the Major Scale. Standing there at the foot of that massive harmony of stone and sound was uncanny and marvellous.

I wandered slowly down the steps. How beautiful it was, the street below and around me, elegant and grey and English, not a depressing grey but a fine, pale, glimmering one, how familiar and present it all felt. There was something profound about it, something just out of reach, like trying to remember something, trying to recall a fading dream upon waking. The city lay spread out all around me from the centre here where I stood, it pulsed with energy, teemed with activity, the activity of my own people, the English, the people who looked most like me and talked like me and heard and saw like me. This city was an expression of and a repository of our multiform character and our way of being and our sense of beauty. There was something here, a pulse, a vibe, whatever you call it, that was plugged into my soul. Nowhere else felt the same. I looked at the people walking by, keeping calm and carrying on amidst the bombardment of sound. A kind of sympathetic yearning rang through my chest and made me smile. A passing girl met my eyes and smiled back, held my eyes for a moment and then withdrew hers and went by, smiling still. I gazed after her, my veins kindling with gold fire. I knew that this was where I would live, in this city, some day; this was where I would spend my life. To move here and live and fall in love and try to create beautiful things, and when I am old, to sit with my hands on a stick in front of me, surrounded by my people, peaceful and content.

Jack and I headed down Ludgate Hill, away from the clamouring bells, towards the westering sun. After a couple of minutes we heard the bells behind us gradually dropping out one by one, until there was only one bell, pealing out, strong and insistent. I turned and saw St Paul’s half-hidden at the end of the street, like an image from every Dickens drama. The bell struck out a final chime that seemed to shiver and wobble among the rooftops and chimneys. By the Old Bailey I turned again and saw half of the frosty grey dome curving proudly above the dazed buildings. The wide street ahead advanced on into sunlit distance. Ludgate Hill became Fleet Street and we went by the tiered white tower of Wren’s St Bride’s Church. Here tall red-brick gabled buildings interspersed with the sooty white stone. Every now and then a big Victorian clock stuck out high up over the street, its shadow slanting over the sunlit stone. A police or ambulance siren oscillated somewhere behind or to the side. Red double-decker buses and black taxi cabs cruised by. We passed old-style taverns, narrow tall ones and stout fat ones, with big windows made of a multitude of small panes and golden figures of jesters or cockerels or bells above the entrance. Outside an old pub called Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese a man was sweeping the pavement, by the chalked blackboard menu, the broom rasping over the stones. I was light-headed with hunger. ‘Shall we have dinner?’ I said. Jack consulted his map. ‘Up ahead there is Temple Bar,’ he said, pointing with his finger. ‘Do you see it?’ At first I couldn’t, but then the dazzle of the sun resolved itself and I saw a distant clock tower, and, beneath it in the street, a weird black shape on a plinth, against the shining sky. ‘I think so,’ I said. ‘That’s the end of the City,’ Jack said. ‘We’ll eat once we get through there, shall we?’ ‘Alright,’ I said. My feet felt battered and crushed and I longed to sit. ‘Somewhere along here is the Temple Church,’ said Jack. ‘I would like to pay a quick visit.’ On we went for a couple of minutes until we stopped by a Tudor-looking building with timber beams and black windows multi-paned like fly’s eyes, over a small archway. “In here,” Jack said. He dodged in through a half-door in the archway and I followed.

Here under the arch was a porter’s lodge like the ones in the old universities in my home town, with cream walls and heavy wooden brown doors. Through we went and out into a narrow paved passage between windows and pale yellow walls. ‘Dr JOHNSON’S BVILDINGS’ read some old lettering up on the right. Ahead were glimpses of sunlit trees and elegant old lamps. The noise of the street faded behind us. The buildings on the left came to an end and through some trees we saw the rounded end of an old church, glowing with a creamy soft sienna-tobacco colour in the warm sun. We walked around the church entrance. Here was a small courtyard with old lamp-posts and paving stones, by the side of the church, whose long rectangular body extended alongside. There was a building with little arches through which could be seen more arches and columns, like a university cloister. All was quiet. We were the only ones there. From a half-open window came the sound of gently clinking cutlery. I wandered around while Jack took photos.

From the hushed cloister I saw quadrangles with trees and neat bushes surrounded by Georgian red-brick buildings, sunlight dancing in silent spangles here and there on the walls and windows. Someone sat on a bench reading a book and smoking. It was odd to be in this realm of quiet and cloistered elegance just a couple of minutes after coming off the rumbling city street. I wanted to explore, but my poor legs and feet and stomach said no.

We went back by the round part of the church and past Dr Johnson’s bvildings and under the arch. The soft roar of the street was striking after the little interlude of tranquillity. We shuffled swiftly on; this was the final stretch now. Feet clopped by, traffic whooshed and rumbled, snatches of talk swirled in and out of hearing. We were approaching the huge Royal Courts of Justice building, the big Victorian clock projecting out high up on its oat-white tower, and down below in the road, the weird shape on a tall plinth that I had seen from a distance. A black form with bat-wings outspread it was, like a Fury, in silhouette against the pale cream of the court building, high up on its dark stone plinth in the middle of the thoroughfare. As we got close I realised I was staring at the back end of a large dragon, the City boundary dragon at Temple Bar. Rampant and fierce, spreading its dragon wings, it stood reared up with its chest, neck, and tail arched and its jaws open as if roaring or breathing fire. With its claws it clutched the City emblem on a shield. Spurring our weary limbs we passed beyond the frightful guardian and were through onto the Strand.

We limped on for a few yards and then slowly sank down on the ground and sat in a doorway with our legs straight out on the pavement. My legs throbbed like a dynamo. We must have walked eight miles at least. People walked constantly past, their legs going briskly by in front of us. Buses snored and huffed at the traffic lights. I sat in a slow daze, my eyes wandering over the walls and windows of the huge court building across the road. As we sat there momentarily crashed out, a group of men came hustling along the pavement from the left, six or seven big men in dark suits moving rapidly and urgently, their eyes darting nervously this way and that, all of them bald and boxer-faced and muscular. They all strode quickly along clustered around an invisible centre, someone within the moving wall of muscle who was being conducted away from the courts and who they were evidently protecting from imminent assassination or abduction. One of the bruisers met my eyes for a second as they went past like giants and then they were gone, hurrying away towards the City.

Eventually I roused and expressed a strong desire for consumption of food and drink. We got up slowly like old men. A few yards down the road we found a convenient tavern, a tall narrow Tudor-looking building, whitewashed with black timber beams and many-paned windows. For the security and comfort of travellers and pilgrims. Warm red-gold light glowed through the myriad of glass rectangles. We went through the open door into the bar, where we were directed upstairs to the dining area. Up we went into a large room with timber beams and a dark wood floor and tables and chairs and a bar along one side, behind which shimmered rows of bottles and glasses. A bright fire was crackling in the grate, there was a cheerful clatter of dishes and cutlery from an open doorway. We sat at a table not far from the windows, which were half-open, the street sounds below rising faintly. We ordered steak and ale pie with potatoes and peas and gravy. Jack wanted to drink Port so we ordered some, which came black-looking in little bell-shaped glasses. It was luscious like dark woodland fruits and strong and warming. Jack went to the bar and bought a half-bottle of Port and we had some more. The area around the bar was beginning to fill up with men in dark coats and hats who were coming in in twos and threes, barristers or lawyers from the courts; the bartenders moved back and forth pouring out red wine or spirits, voices of men called and boomed good-naturedly. They pressed at the bar, talking and laughing, their hats like puddings crowding around, their noise pleasant and eager and amiable. Glasses and bottles clinked.

Maids in white aprons brought our dinner. The large plates were filled to the edges with blocks of pie with golden-brown crust, thick rich gravy, peas, steaming baby potatoes smothered in butter. Oh yes, yes. I shook pepper over the pie and gravy, a dash of vinegar on the peas as was my wont, and started in. It was hot and rich and splendid. Neither of us said a word for fifteen minutes as we scoffed this glorious fare. I was so hungry that eating this food seemed like a sort of miracle. I sat in a kind of trance, experiencing with wonder this miraculous eating. The men at the bar, warmed and mellowed by liquor and wine, settled their voices into a pleasing, sonorous, continuous chatter.

Finally I mopped up the remaining gravy with chunks of bread and leaned back with a sigh. Nothing was left on our plates. We sat for a time as if dazed. Then we poured out some more Port and lit cigarettes. The fire in the grate was built up with more wood. We watched the cigarette smoke slowly turning and coiling and drifting towards the windows. Outside deep evening was beginning to come on. The curtains moved gently in a slight breeze. Candles burned in the small iron chandeliers that hung from the timbered ceiling. Subtle shadows danced on the walls. Jack sent a slow silent smoke ring wheeling up to the timbers. A warm golden sensation was suffusing through my blood and my limbs. The melodious, gentlemanly chatter of the men flowed on. I sipped the dark fruity wine and gazed at a framed nineteenth-century picture of a farmer in hat and breeches sowing seeds in a furrowed field.

More people came in. Lamps were lit. The staff moved here and there with trays of food and drink. We had more Port. We began to talk. We talked of London and Charles Dickens and Pink Floyd and Monty Python and the Knights Templar and Freemasonry and other things. We sat long at the table talking and sipping and smoking, until the wine ran dry and the bill arrived on a saucer with two little madeleine cakes in plastic wrappers. I grasped one of the shell-shaped cakes and slipped it into my pocket for later. We stood unsteadily. Jack went off to pay while I navigated past the fireplace and through the doorway and down the narrow staircase. The stairs seemed to soften and bend under my feet and I had to feel my way down with my palms and fingers touching the walls.

As I went out onto the street John Cleese walked past me, passing two feet away, tall and moustached, going towards Aldwych. If it wasn’t him it was his double. I stood amazed for a moment, looking after the tall ambling form. Something struck me as really funny and I started laughing. I didn’t know what I was laughing at but I couldn’t help it. Jack came out and found me leaning against the wall shaking with laughter. I told him that John Cleese just walked past me and he started to laugh too, although I don’t think he believed me. “That’s him over there,” I said, shaking helplessly, pointing down the street at the distant lanky figure. Jack looked and burst out in a loud guffaw. I swooned with laughter, clinging to a lamp-post. People walked by blank-faced.

‘Where do you think he’s going?’ asked Jack.

‘Down the Strand,’ I said.

‘What for?’ he asked.

‘To have a banana,’ I said.

We folded up in a paroxysm of laughter, our eyes swimming over, helplessly juddering with mirth, until gradually it subsided and the fit passed.

‘Dearie me,’ I said, wiping tears off my cheeks.

We walked on, grinning. Jack was a good bloke. He was alright, Jack. We had heard the chimes at midnight. Well, not exactly midnight, but near enough. It had been a good day. We would be out again tomorrow, in London, somewhere else. We weaved past St Clements’ Church. Here was the statue of Samuel Johnson, frowning over his book. When a man, Sir, tires of London, he tires of life. The city teemed on all around us. We were near Covent Garden again. The theatres, pubs and restaurants were lighting up. Buses and taxis throbbed by. The sun was sinking and darker clouds were pressing in from behind, from the east. We turned left and came out onto Waterloo Bridge and gazed at last upon the Thames.

We stood in silence halfway across the bridge and smoked the last cigarettes. The immense evening struck steadily and softly upon us. The sky to the west was a final cool indigo blue as the sun sank below the horizon. The tower of Big Ben stood there with its clock glowing faintly like a moon, and Westminster Abbey’s turrets in silhouette. The mighty river, broad and grey, lay spread all around below us. A small boat cruised slowly from under the bridge towards Westminster. Traffic roared and rumbled steadily past us on the bridge. Lights flared or twinkled across on the south bank, the city seemed to give off an electromagnetic crackle in the air. Behind us, down the river to the east, was the silent grey dome of St Paul’s, that familiar image seen now present and alive in the pulsing evening. My body ached with fatigue but also rang with excitement. I felt like we had been somewhere today. We had gone somewhere and come back, we had seen something of the blood and bones and ashes of the city. And here we were.

Jack had spotted Cleopatra’s Needle far down there on the Embankment. We found the steps to the street and went carefully down them. The street lamps on the Embankment were coming on, the gold light igniting within the glass globes, and the lines of gold bulbs that were strung between the lamps. We crossed over the road and walked on until we came to the narrow grey stone column soaring up on its pedestal. Smiling sphinxes flanked the obelisk, facing in towards it. The stone glimmered in the last light of the sun, marked all the way up with hieroglyphics.

‘Blimey,’ said Jack, looking up at the base of the stone eight feet or so up. ‘Too high to reach.’

The sphinxes smirked at his disappointment. Jack went around taking photos, his camera clicking and whirring. I scrambled up onto the sooty stone pedestal of one of the sphinxes and sat between the bronze paws, beneath the smiling face.

So...is anyone else going to read this and engage with it?

It's been up for two months now, and only one comment.

Is anyone going to read this? Does it go on a public board or something?